Things to do in Portland when you're sick: Benchmarking Cryptographically Secure RNGs

Posted 13 May 2013 by Thomas M. DuBuissonRandom number generation isn't something that non-computer scientists or cryptographers think about very much. The fact is, it's a critical task for almost any secure system - keys, nonces, and passwords all need some entropy and that has to come from somehwere.

It is actually hard to design generators that give random or seemingly random values. It's harder to do so in a cryptographically secure manner - meaning that there is no practical way to predict part of the output even when given all previous or future values. It's even harder to design a generator that has high performance. If you find the task easy then you can probably make a good living writing research papers on the topic.

To complicate matters further, the dimensions for comparison are more than security and performance:

Determinism: Most RNGs are pseudo-random - the output is based entirely on their initial seed. This is a useful feature as it allows separate entities to obtain the same random stream without significant communication.

Backtracking Resistance: compromise of a future generator does not yield the adversary any ability to compute previous random values.

Prediction Resistance: even if the adversary has obtained one state of the RNG they might not be able to predict the future output because the generator can continually incorporate entropy from outside sources.

Fortunately, the world is large and, even in a language that fancies itself a niche, there are options. There are at least four packages on Hackage that are worth trying and the generators available in these packages fit into three catagories:

- Block-Ciphers in counter or quasi-counter mode

- NIST Standards Based (HMAC, hash, and cipher-based generators)

- External Entropy (operating system backed, RDRAND when available)

- crypto-api (using a pre-release version of entropy)

Intel-AES

Based on Intel's AES-NI example code, this package is a fast AES in counter mode. There is no backtracking resistance. It also doesn't currently build due to recent changes to crypto-api, but feel free to try my fixed up git repository.

CPRNG-AES

This is also an AES without backtracking resistance. Oddly, this is not AES in counter mode, it XORs a counter with the previously returned random bytes to obtain the IV. This isn't the only oddity either; for all practical purposes there isn't any reseeding happening inside of CPRNG-AES, nor are there explicit notifications when reseeding is needed. The reason for these deviations from accepted practice is unknown.

CPRNG-AES is more popular than intel-aes, probably due to its cleaner build system and early arrival on Hackage.

Deterministic Random Bit Generator (DRBG)

DRBG is a collection of generators and modifiers. These generators are all naive English-to-Haskell translations of NIST SP 800-90. Included are Hash-based, HMAC-based, and a counter based generators. These generators are all backtracking resistant and allow additional input to be provided for prediction resistance. Modifiers take as input one or more generators and produce a new generator; the modifiers include automatically reseeding one generator with another, buffering generators, and XORing the output of two generators. The modifiers are all custom solutions, but the underlying generators successfully complete the NIST Known Answer Tests.

Crypto-API and Entropy

Crypto-api provides access to a "system generator" which actually uses either a system source like /dev/urandom or Intel's RDRAND instruction. Lumping this generator in with the above is questionable at best - the above generators are pseudo-random and result in the same output when given the same seed. The SystemRandom generator is IO-based and anything it generates is not reproducable - it's more like reading lazily from an infinitely long file.

Benchmarks

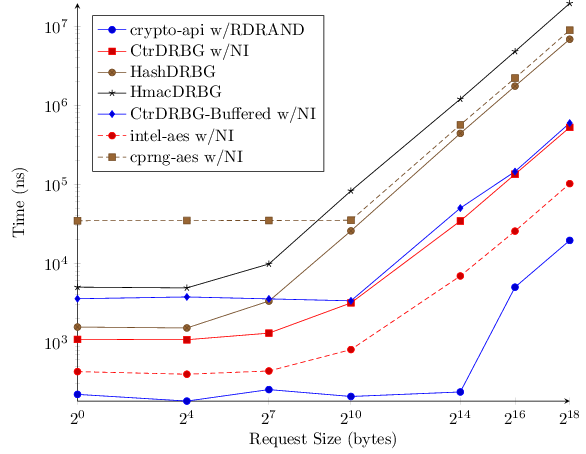

Since all of these generators can be incorporated into a project with near-identical ease, and most users aren't concerned with adherence to standards or other quasi-security arguments, the main difference remaining is performance. I've benchmarked six generators over a range of data-request sizes. The results will hopefully educate potential users about their choices as well as motivate continued development.

I'll present the mean values in the graph. This is slightly misleading as some generators, such as the buffered generators, have very odd densities, so take your grain of salt.

(all benchmarks are on an 3.1GhZ laptop with AES-NI and RDRAND)

Looking these numbers I have the following observations:

It appears CPRNG performs buffering - news to me.

Buffering isn't properly shown-off by the benchmark - making CPRNG and CtrDRBG-Buffered look bad. Acquiring one byte one-hundred times still reflects the initial measure of generating our potentially multi-megabyte buffer. In real use cases I expect buffering, to be a nice boon.

Intel-AES is amazingly fast. I knew the AES routines relied on by CtrDRBG and CPRNG were sub-par but not to this extent.

RDRAND, via SystemRandom, is far and away the best performing generator (assuming your system supports the instruction).

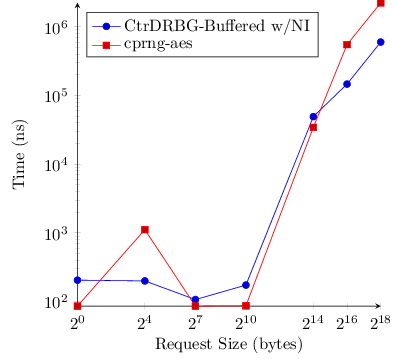

I re-ran the benchmarks, stepping the buffering generators one byte first. This means they get the advantage of precomputing an arbitrary number of bytes up front and just taking bytes off a bytestring to serve requests. The purpuse here is just to confirm we are talking about mere nanoseconds unless the generators need to compute more random data for the buffer.

Conclusion

All of these packages have shown reasonable performance and include simple APIs (via the RandomAPI and CryptoRandomGen classes). The one hitch that bothers me with any of them is a lack of reseeding in the RandomAPI and CPRNG-AES.

Unless you need top-notch performance (in which case, use SystemRandom or Intel-AES), you'll probably be well served by selecting a package based on features and portability.