The Type-Safe Jabberwolk

Welcome to my blog! This is a collection of posts about cryptography, Haskell, and other technical topics.

Posts

- Applying Cryptol To Tantrix - December 25, 2015

- Secure Computation with HELib - May 13, 2013

- Benchmarking Cryptographically Secure RNGs - May 13, 2013

- Easy, threadsafe, communications security for Haskell - April 28, 2013

- License Plate Recognition With Haskell and OpenCV - April 28, 2013

Applying Cryptol To Tantrix

Posted 25 December 2015 by Thomas M. DuBuisson

I just noticed John Carmack’s tweet about solving the Tantrix puzzle in Racket. I like solving puzzles with Cryptol and this seemed like a good opportunity for a non-cherry-picked problem.

Cryptol?

Cryptol started as a domain specific language for cryptography. It has native support for arbitrary bit-width words and a built in bridge to automated (SMT) solvers. Each word is represented as a bit array which can be trivially permuted, split, joined, and indexed. These days, many people think of Cryptol as a convenient high-level language for running SAT or SMT solvers.

Tantrix?

I didn’t know what Tantrix was, but the above link has a decent explanation. In short, there are ten hexagonal shaped puzzle pieces with 3 different colored lines on each. The task is to make a loop out of a particular color using a particular number of tiles. For example, it should be simple to use three tiles and create a loop for the yellow line.

Solution Strategy

In contrast with general purpose languages in which you’d probably make an A* or similar search procedure, the solution strategy with Cryptol is almost always to describe the problem and define a boolean test that returns true for a valid solution. After we have a way to recognize the final solution just ask one of the satisfiability solvers to find the assignment that makes this function return true.

A more subtle contrast illuminates the method along with its relative strengths and weaknesses. Solutions that use SAT to recognize a valid solution require the developer to make an exhaustive set of rules or checks for each necessary condition. Solutions involving construction, testing, and back-tracking search encode some requirements implicitly in the construction and omit some checks in the final valid solution test. As a result, it can be conceptually hard to identify and write all necessary constraints of the solution but the reward is a concise description of valid solutions that is more amenable to later adjustment or application to related problems.

Onward to Cryptol and Glory

We’ve established that we’ll be defining the Tantrix puzzle in Cryptol then using SAT to find the valid solution, so let’s get to it. First we need to define the puzzle pieces and some basic operations.

Since there are only three colors we’ll use 2 bits for color:

type Color = [2]

type Tile = [6]Color

Our puzzle has ten hexagonal tiles. Each Tile has three colored lines connecting two of the sides. Each side has exactly one color. Borrowing significantly from John Carmack’s code mentioned in the introduction, our pieces start with the right-most color and go clock-wise from there.

tiles : [10]Tile

tiles = [ [r, y, y, b, r, b]

, [b, r, r, b, y, y]

, [r, r, b, b, y, y]

, [b, r, y, b, y, r]

, [r, y, y, r, b, b]

, [y, b, r, y, r, b]

, [r, b, b, y, r, y]

, [y, b, b, r, y, r]

, [r, b, y, r, y, b]

, [b, y, y, r, b, r]

]

where (r,b,y) = (red,blue,yellow)

red,blue,yellow : Color

(red,blue,yellow) = (0,1,2)

Placements, the below Pt type, are a collection of a tile, location on the grid, and a rotation.

type Pos = ([8],[8])

type Dir = [3]

type Rot = Dir

type Pt = (Pos,Tile,Rot)

// Completed boards are n placements

type Board n = [n]Pt

We can now add some simple helper functions to obtain the neighbor positions, test for neighbors, and get the color of a particular placed piece at a particular point (0 is right, working clockwise).

directions : [6]Dir

directions = [0..5]

neighbor : Pos -> Dir -> Pos

neighbor (x,y) dir = ns @ dir

where

ns = [ (x+1, y )

, (x+1, y-1)

, (x, y-1)

, (x-1, y )

, (x-1, y+1)

, (x, y+1)

]

isAdjacent : Pos -> Pos -> Bit

isAdjacent p0 p1 = or [neighbor p0 d == p1 | d <- directions] && noOverflow

where

noOverflow = and [~zero != v | v <- [p0.0,p0.1,p1.0,p1.1] ]

dirColor : Dir -> Pt -> Color

dirColor dir (_l, tile, rot) = tile @ ((extend dir + extend rot : [4]) % 6)

We’ve ran across our first gotchas! A first attempt might check adjacency and calculate dirColor through simple arithmetic such as a.x == b.x + 1 but that doesn’t account for overflow. Without these checks SAT will result in more interesting solutions than most people like. In the case of adjacency we cheat by not allowing the maximum index and use an excessively large grid.

Now that we have the structure, the solution starts to deviate from what Carmack pasted. What’s left for us is not a construction of lines and tree search but “merely” describing a valid board. Valid boards for a given color have to 1. Have only valid placements 2. Use each tile only once 3. No tiles overlap 4. when considering the line it must form a loop. Let’s focus on the first three and break 4 down in a minute.

Step 1: Placement validation is a check that each tile is from the original game - the tiles array.

Steps 2 and 3: Uniqueness testing of the tiles, their positions, or anything else can be done in a few ways. Conceptually we can just test each element for equality with all elements in the set and ensure only one was equal (e.g. to itself). While this appears inefficient two things to remember are that this toy problem is small and there is an army of optimizations just under the surface. We do have to pay the cost of syntactically reforming the problem but many duplicated and excess terms will be handled by the solver.

We also require the board to include the origin. Requiring a tile at the origin is without loss of generality (I think) because the whole board can be rotated till a tile fits in the origin’s corner, but I have not proven this to be the case.

validSolution : {n} (n >= 3, n <= 10) => Color -> Board n -> Bit

validSolution c brd =

hasOrigin && validTileSet brd &&

uniquePositions brd && boardIsLoop c brd

where

validTileSet bs = unique && fromBag

where unique = and [ uniquely (\x -> x.1 == b.1) bs | b <- bs ]

fromBag = and [ elem b.1 tiles | b <- bs ]

uniquePositions bs = and [uniquely (\x -> x.0 == b.0) bs | b <- bs]

hasOrigin = or [b.0 == zero | b <- brd]

The simplest method I found for loop checking breaks the problem down in three ways 1. Ensure the board is ordered such that each tile adjacent in the array is conceptually adjacent on the board 2. Walking the path forward from the current tile, the direction of the next neighbor is also a direction of the color of interest 3. Walking the path backward from the current tile, the direction of the neighbor is also the direction of the color of interest.

All three of these requirements can be expressed by the same path traversal that takes a predicate and tests every pair of neighbors. We must make sure the last tile and first tile are paired too so we have a loop instead of an uninterrupted line. I handled this with an excessive, but sufficient, extra lap around the loop.

boardIsLoop : {n} (fin n, n >= 3, n <= 10) => Color -> Board n -> Bit

boardIsLoop c bs =

forPath adjacentPl bs &&

forPath colorsMatch bs &&

forPath colorsMatch (reverse bs)

where

forPath pred xs = and [pred b0 b1 | b0 <- (xs # xs)

| b1 <- drop `{1} (xs # xs) ]

adjacentPl a b = isAdjacent a.0 b.0

colorsMatch a b = and [b.0 == neighbor a.0 d ==> dirColor d a == c

| d <- directions]

And that’s the entirety of the solution. We can get a little prettier (and smaller) by 1. Pushing lots of the helper functions into Cryptol and 2. Defining a pretty printing function. Item 1 is done - pull request 299 on github and would benefit actual project, not just toys. Cryptol needs a larger Prelude. Item 2 is small unless you want something graphical or colored text, which Cryptol as a DSL can not do. My pretty printer performs the rotations and presents the color values in a normalized form:

pretty : {n} (fin n) => Board n -> [n](Pos, [6]Color)

pretty bs = [ (b.0, b.1 <<< b.2) | b <- bs ]

Now we can run code to obtain solutions:

:sat (validSolution `{3} yellow)

pretty (it.arg1)

[((0x00, 0x01), [0x0, 0x2, 0x2, 0x1, 0x0, 0x1]),

((0x00, 0x00), [0x2, 0x0, 0x1, 0x1, 0x0, 0x2]),

((0x01, 0x00), [0x0, 0x0, 0x1, 0x2, 0x2, 0x1])]

Solving all 10 versions of the problem takes a heart-beat. Not surprising, but fun and educational for the kids at Christmas.

Secure Computation with HELib

Posted 13 May 2013 by Thomas M. DuBuisson

Homomorphic encryption is a hot new area of study and discussion in the world of cryptography. Using homormorphic encryption it is possible to produce ciphertexts on which an arbitrary third party (ex: Amazon) can perform computations despite the encryption. That is to say, if you have a secret (\(pt\)) and homomorphically encrypt it then an operation \(f\) can be performed on the cipher text such that \(decrypt(f(encrypt(pt))) = f(pt)\).

This result is truly stunning, but singing the praises, perils, and history of fully, somewhat, semi, or leveled homomorphic encryption is not what this post is about. You can Google for the cool implications but today I’m going to talk about a particular open-source homomorphic encryption library (written in C++) called HELib.

What is HELib?

HELib implements a homormophic encryption scheme. This library is open source on github and, from a popularity perspective, has really taken off for an obscure crypto library - having over 500 watchers.

Unlike some earlier HE schemes, HELib uses a SIMD-like optimization known as ciphertext packing. As a result, each individual ciphertext element with which you can perform a computation (addition or multiplication) is conceptually a vector of encrypted plaintext integrals. Thus, this scheme is particularly effective with problems that can benefit from some level of parallel computation.

Example Use of HELib

Folks on github have asked Shai to produce a tutorial showing how to take HELib and perform basic computations such as \(2+2\). As awesome as Shai and Victor are, I don’t expect them to find time to fill this request. Hopefully this section of the blog will suffice for most people. This is more of an HELib quick start guide and absolutely not an FHE primer, there is lots of text on FHE but not much on getting started with HELib.

Lets start with an example that fills two vectors with integrals, encrypts them homomorphically, and performs component-wise addition and multiplication. This process is actually more involved, the real steps we will go through are: declare our parameters (plaintext space, levels, columns, secret key haming weight, security), generate a secret key, obtain an EncryptedArray, which is a class that aids in later computations, encrypt our vectors, perform addition and multiplication, decrypt the results and print.

Without further ado, lets dive in. NOTE: all this code is based on one of HELibs ‘Test_*.cpp’ examples.

First some boiler-plate that is already discussed or self explainitory.

#include "FHE.h"

#include "EncryptedArray.h"

#include <NTL/lzz_pXFactoring.h>

#include <fstream>

#include <sstream>

#include <sys/time.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

/* On our trusted system we generate a new key

* (or read one in) and encrypt the secret data set.

*/

long m=0, p=2, r=1; // Native plaintext space

// Computations will be 'modulo p'

long L=16; // Levels

long c=3; // Columns in key switching matrix

long w=64; // Hamming weight of secret key

long d=0;

long security = 128;

ZZX G;

m = FindM(security,L,c,p, d, 0, 0);

Notice the parameter names are pretty consistent in HELib examples as well as the literature. In this case, I am building for GF(2) - so my homormorphic addition is XOR and multiplication is AND. Changing this is as easy as changing the value of p. Folks wanting to see 2+2=4 should set p to something that matches their desired domain, such as 257 to obtain 8 bit Ints.

NOTE: I ran into a bug with p=65537 and had to manually set m to an acceptable value, 65539, because FindM() failed.

Now lets use these parameters to build a private key - HELib is evidently asymmetric in addition to being homomorphic, wow!

FHEcontext context(m, p, r);

// initialize context

buildModChain(context, L, c);

// modify the context, adding primes to the modulus chain

FHESecKey secretKey(context);

// construct a secret key structure

const FHEPubKey& publicKey = secretKey;

// an "upcast": FHESecKey is a subclass of FHEPubKey

//if(0 == d)

G = context.alMod.getFactorsOverZZ()[0];

secretKey.GenSecKey(w);

// actually generate a secret key with Hamming weight w

addSome1DMatrices(secretKey);

cout << "Generated key" << endl;

We have now generated a secret key. Notice the public key was extracted from the private key - this is C++, that isn’t just an alias. Interestingly, a public key in this context need only be an encryption of “1”.

Lets get our helper class instantiated:

EncryptedArray ea(context, G);

// constuct an Encrypted array object ea that is

// associated with the given context and the polynomial G

long nslots = ea.size();

I find having an nslots value around is useful. You can’t pick the number of slots (plaintext elements) a ciphertext can hold, but you can learn what parameters control this value and try to optimize for your situation. Now for encryption.

vector<long> v1;

for(int i = 0 ; i < nslots; i++) {

v1.push_back(i*2);

}

Ctxt ct1(publicKey);

ea.encrypt(ct1, publicKey, v1);

vector<long> v2;

Ctxt ct2(publicKey);

for(int i = 0 ; i < nslots; i++) {

v2.push_back(i*3);

}

ea.encrypt(ct2, publicKey, v2);

Well that was just some verbose C++ with calls to EncryptedArray::encrypt() hidden within. Hopefully by this point the notion has sunk in that we are talking about a whole vector of plaintext values (v1, v2) that are placed into individual ciphertexts (ct1, ct2).

Lets see some SIMD style computation!

// On the public (untrusted) system we

// can now perform our computation

Ctxt ctSum = ct1;

Ctxt ctProd = ct1;

ctSum += ct2;

ctProd *= ct2;

Well damn, that was anti-climactic. When you think about it, it should be almost disappointingly easy if this library is as awesome as I hope I hyped you up to expect.

Finally, we will decrypt the sum and product results:

vector<long> res;

ea.decrypt(ctSum, secretKey, res);

cout << "All computations are modulo " << p << "." << endl;

for(int i = 0; i < res.size(); i ++) {

cout << v1[i] << " + " << v2[i] << " = " << res[i] << endl;

}

ea.decrypt(ctProd, secretKey, res);

for(int i = 0; i < res.size(); i ++) {

cout << v1[i] << " * " << v2[i] << " = " << res[i] << endl;

}

return 0;

}

And that’s it - under one hundred lines and you have a program that can add, multiply, subtract, and negate (see the header files) data without even knowing the values.

Performance

The performance of addition and multiplication varies by level, security, and plaintext characteristics (ex: word size). For the example, I get timings of:

| Modulus | Number of Slots | Time for addition (ms) | Time for multiplication (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 257 | 44 | 0.7 | 39 |

| 8209 | 22 | 0.7 | 38 |

| 65537 | 2 | 2.9 | 177 |

It is worth once-again pointing out that this is running on top of NTL, which isn’t thread safe. While you get some “parallelism” from the ciphertext packing you can’t take easy advantage of multiple cores without multiple processes.

Noise in the CipherText

Each operation, but most notably multiply, results in a ciphertext that is more “noisy” than its inputs. Too much noise and your decryption will fail (producing results that don’t match your intended computation). Thus, FHE computations have a notion of depth much like a circuit depth. If you exceed a given depth then the noise inherent to the computation will become great enough that decryption can result in errors. The trick is to know your current depth, for any given ciphertext, and perform a recrypt operation that produces a ciphertext of identical meaning but with reduced noise. However, recrypt is computationally expensive so performing it only when needed is critical.

One way to reduce the number of recrypt operations is to increase the “levels” parameter (L in the above example). There is a trade-off with the depth and how often you recrypt - computing over ciphertexts that support more levels is itself more computationally expensive.

HELib doesn’t currently support a recrypt operation, so you are simply not able to perform computations of significant depth - saving you from the misery of determining a good balance between levels and recryption. This does, however, make noise management critical as you simply are not able to perform computations that require significant depth.

Noise Management

I just told you that FHE operations produce ciphertexts that build up noise and this noise prevents decryption. Furthermore, in HELib (as it stands today) this causes a limit to the depth of the computations you can practically perform. As a result, you, the programmer, must be intelligent with respect to your algorithms and how they combine ciphertexts.

For example, if you wish to acquire the product of an array of ciphertexts (which are themselves arrays of slots) you could perform what is known in functional programming as a fold - a for loop taking a zero element and adding each element in the array. An implementation can be seen below, this is horrible as it causes \(O(n)\) noise, where \(n\) is the length of the array.

int mulEntireArray( Ctxt &res

, const vector<Ctxt> input

, const EncryptedArray &ea)

{

const int nrElem = input.size();

if(nrElem > 0) {

res = input[0];

for(int i = 1; i < nrElem; i++) {

res.multiplyBy(input[i]);

}

return 0;

}

return (-1);

}

Instead you should use a divide and conquer algorithm, cutting the array in half in each iteration and multiply the two haves, terminating with an array of length one. This results in \(O(lg(n))\) noise. Below is a display version that uses tail calls, likely not using memory in anything approaching a wise manner in C++ but it makes for easy reading.

int mulEntireArray_logNoise( Ctxt &res

, const vector<Ctxt> input

, const EncryptedArray &ea)

{

const size_t nrElem = input.size();

if(nrElem > 1) {

vector<Ctxt> tmp( (nrElem+1)/2

, Ctxt(input[0].getPubKey()));

const size_t sz = tmp.size();

for(int i=0 ; i < sz; i++) {

tmp[i] = input[i];

}

for(int i=0 ; i < sz && (sz + i) < nrElem; i++) {

tmp[i].multiplyBy(input[sz + i]);

}

mulEntireArray_logNoise(res, tmp, ea);

}

else

res = input[0];

return 0;

}

The important part of the above is that tmp copies the first half of input and multiplies by the second half, terminating when it has a one element vector.

Minor Details: Building and the Like

HELib currently exists only as a git repository, there is no distribution package or Windows installer. What’s more, it depends on a new version of NTL (6.0) that is not packaged by many distributions. To get going, you are going to need to download and install NTL, git clone HELib, build HELib remembering to link it against the new NTL and then build your application.

For *nix users, the NTL portion should be as simple as:

wget http://www.shoup.net/ntl/ntl-6.0.0.tar.gz

tar xzf ntl-6.0.0.tar.gz

cd ntl-6.0.0

./configure && make && sudo make install # or something like this

Then to get and build HELib:

git clone git://github.com/shaih/HElib.git

cd HElib/src

# Edit the Makefile as needed

# It already had the correct -I and -L paths for me

make

Now you can write your application and compile it via:

g++ App.cpp $HELib/src/fhe.a -I$HELib/src -o App \

-L/usr/local/lib -lntl

Future

HELib is a young library in a rather young field of cryptography. It blows my mind that the library is so well formed at this point. Hopefully we will see serious contributors and an active community.

If anyone is interested in either making Haskell bindings or porting it to using something thread safe (not NTL) then I’d be interested and would likely contribute, so get in touch.

Things to do in Portland when you’re sick: Benchmarking Cryptographically Secure RNGs

Posted 13 May 2013 by Thomas M. DuBuisson

Random number generation isn’t something that non-computer scientists or cryptographers think about very much. The fact is, it’s a critical task for almost any secure system - keys, nonces, and passwords all need some entropy and that has to come from somehwere.

It is actually hard to design generators that give random or seemingly random values. It’s harder to do so in a cryptographically secure manner - meaning that there is no practical way to predict part of the output even when given all previous or future values. It’s even harder to design a generator that has high performance. If you find the task easy then you can probably make a good living writing research papers on the topic.

To complicate matters further, the dimensions for comparison are more than security and performance:

-

Determinism: Most RNGs are pseudo-random - the output is based entirely on their initial seed. This is a useful feature as it allows separate entities to obtain the same random stream without significant communication.

-

Backtracking Resistance: compromise of a future generator does not yield the adversary any ability to compute previous random values.

-

Prediction Resistance: even if the adversary has obtained one state of the RNG they might not be able to predict the future output because the generator can continually incorporate entropy from outside sources.

Fortunately, the world is large and, even in a language that fancies itself a niche, there are options. There are at least four packages on Hackage that are worth trying and the generators available in these packages fit into three catagories:

- Block-Ciphers in counter or quasi-counter mode

- NIST Standards Based (HMAC, hash, and cipher-based generators)

- External Entropy (operating system backed, RDRAND when available)

- crypto-api (using a pre-release version of entropy)

Intel-AES

Based on Intel’s AES-NI example code, this package is a fast AES in counter mode. There is no backtracking resistance. It also doesn’t currently build due to recent changes to crypto-api, but feel free to try my fixed up git repository.

CPRNG-AES

This is also an AES without backtracking resistance. Oddly, this is not AES in counter mode, it XORs a counter with the previously returned random bytes to obtain the IV. This isn’t the only oddity either; for all practical purposes there isn’t any reseeding happening inside of CPRNG-AES, nor are there explicit notifications when reseeding is needed. The reason for these deviations from accepted practice is unknown.

CPRNG-AES is more popular than intel-aes, probably due to its cleaner build system and early arrival on Hackage.

Deterministic Random Bit Generator (DRBG)

DRBG is a collection of generators and modifiers. These generators are all naive English-to-Haskell translations of NIST SP 800-90. Included are Hash-based, HMAC-based, and a counter based generators. These generators are all backtracking resistant and allow additional input to be provided for prediction resistance. Modifiers take as input one or more generators and produce a new generator; the modifiers include automatically reseeding one generator with another, buffering generators, and XORing the output of two generators. The modifiers are all custom solutions, but the underlying generators successfully complete the NIST Known Answer Tests.

Crypto-API and Entropy

Crypto-api provides access to a “system generator” which actually uses either a system source like /dev/urandom or Intel’s RDRAND instruction. Lumping this generator in with the above is questionable at best - the above generators are pseudo-random and result in the same output when given the same seed. The SystemRandom generator is IO-based and anything it generates is not reproducable - it’s more like reading lazily from an infinitely long file.

Benchmarks

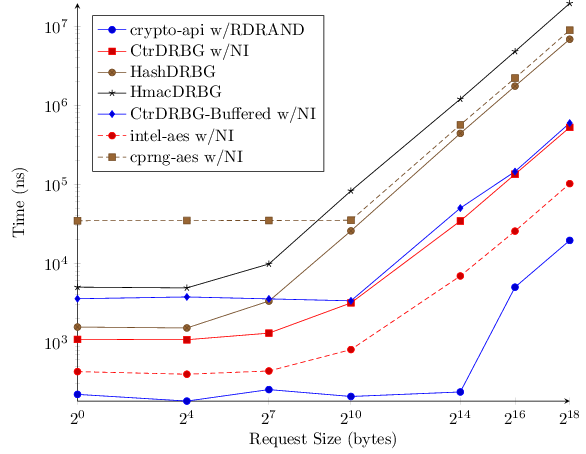

Since all of these generators can be incorporated into a project with near-identical ease, and most users aren’t concerned with adherence to standards or other quasi-security arguments, the main difference remaining is performance. I’ve benchmarked six generators over a range of data-request sizes. The results will hopefully educate potential users about their choices as well as motivate continued development.

I’ll present the mean values in the graph. This is slightly misleading as some generators, such as the buffered generators, have very odd densities, so take your grain of salt.

(all benchmarks are on an 3.1GhZ laptop with AES-NI and RDRAND)

Looking these numbers I have the following observations:

-

It appears CPRNG performs buffering - news to me.

-

Buffering isn’t properly shown-off by the benchmark - making CPRNG and CtrDRBG-Buffered look bad. Acquiring one byte one-hundred times still reflects the initial measure of generating our potentially multi-megabyte buffer. In real use cases I expect buffering, to be a nice boon.

-

Intel-AES is amazingly fast. I knew the AES routines relied on by CtrDRBG and CPRNG were sub-par but not to this extent.

-

RDRAND, via SystemRandom, is far and away the best performing generator (assuming your system supports the instruction).

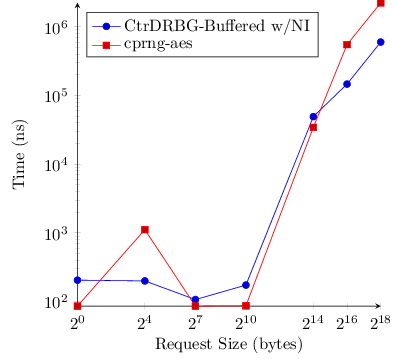

I re-ran the benchmarks, stepping the buffering generators one byte first. This means they get the advantage of precomputing an arbitrary number of bytes up front and just taking bytes off a bytestring to serve requests. The purpuse here is just to confirm we are talking about mere nanoseconds unless the generators need to compute more random data for the buffer.

Conclusion

All of these packages have shown reasonable performance and include simple APIs (via the RandomAPI and CryptoRandomGen classes). The one hitch that bothers me with any of them is a lack of reseeding in the RandomAPI and CPRNG-AES.

Unless you need top-notch performance (in which case, use SystemRandom or Intel-AES), you’ll probably be well served by selecting a package based on features and portability.

Easy, threadsafe, communications security for Haskell

Posted 28 April 2013 by Thomas M. DuBuisson

Introduction

Obtaining an encrypted and authenticated communication channel in Haskell has, sadly, proven to be more complex than necessary. Over the past few years I’ve observed people using cryptographic primitives to roll their own solution and some people have made custom higher level libraries that often bring in additional C-library dependencies, restrictions such as thread safety, or even both. Another solution might be to glue together two of the many client and server TLS libraries, but I haven’t seen any one library that supports both client and server; there’s also a lack of information about interoperability, performance, and ease of use when combining two libraries.

For these reasons I have created the commsec and commsec-keyexchange packages that allow for authenticated, integrity and confidentiallity protected, communications.

Guts of the Library

CommSec

The CommSec library sends and receives information in datagrams much like how IPSec ESP works. Each plaintext sending is transmitted as \([ LEN | IV | CT | TAG ]\) where LEN is a 4 byte length encoding of the message size (not including itself), IV is the 8 byte counter, CT is the AES GCM encryption of the plaintext under said counter, and TAG is the GCM authentication tag.

CommSec Key Exchange

The key exchange is based on the RSA-authenticated station to station protocol. This is just an authenticated DH scheme: each side generates \(x (\bmod p)\) and \(y(\bmod p)\), where \(p\) is a public large prime. They compute and share \(a^x\) and \(a^y\), where \(a\) is a generator. We then have shared secret \(a^{xy}\) by computing \((a^x)^y\) or \((a^y)^x\). The result is then verified using an RSA signature, transferring \(\text{AES-CTR}(RSA(a^x, a^y))\) where the AES key is derived from the newly shared secret and each party uses their own private key for signing.

Use

You first need to generate RSA keys and share the public key between your communicating systems:

$ ssh-keygen

...enter a path...

After that you can using commsec-keyexchange to perform an authenticated key exchange and send/recv data.

import Crypto.PubKey.OpenSsh

import qualified Data.ByteString as B

import Network.CommSec.KeyExchange

main = do

-- Step 1: (not shown) Get file paths, host, and port.

-- Step 2: Read in the keys

let dec d f = ether error id . d `fmap` B.readFile f

OpenSshPrivateKeyRsa priv <- dec decodePrivate myPrivateKeyFile

OpenSshPublicKeyRsa them _ <- dec decodePublic theirPublicKeyFile

The first thing we do is obtain the RSA keys - our private key and their public key.

-- Step 3: Listen for and accept a connection

-- (alternatively: connect to a listener).

ctx <- if doAccept

then accept host port them priv

else connect host port them priv

After that we can perform a key exchange, which allows establishes a socket and shared key.

-- Step 4: Use the communication contexts along with

-- the send and recv primitives to communicate.

send ctx "Hello!"

recv ctx >>= print

Performance Comparison

I benchmarked commsec to compare with the package I am replacing, secure-sockets:

| Package (sending+recv) | Size (Bytes) | Time (us) |

|---|---|---|

| CommSec | 16 | 10 |

| CommSec | 2048 | 76 |

| secure-sockets package | 16 | 29 |

| secure-sockets package | 2048 | 40 |

These results aren’t surprising. The design of commsec means it probably has lower overhead costs, but the GCM routines aren’t as well optimized. This means that commsec will be faster on the small packets while secure-sockets is faster on larger messages (until I switch to a faster AES routine or someone optimizes the current one).

End Notes

These libraries come with very strong warning: there is no guarentee of correctness. These libraries were not developed with any rigor or peer review!

As part of the build-up to this package, additional work was done on the crypto-pubkey-openssh package to ensure we could use ssh RSA keys generated from your typical ssh-keygen command, as well as work on a cipher-aes derivative to improve the throughput for small messages.

License Plate Recognition With Haskell and OpenCV

Posted 28 April 2013 by Thomas M. DuBuisson

Introduction

Over the past week I have expored the topic of automatic license plate recognition. While it is basically a solved problem, the area of image processing has always intigued me and the plethora of literature made LPR seem a good place to start. Take note: I don’t know anything about image recognition! What is an integral image? What is a white hat transformation? Until recently I had no idea.

OpenCV is clearly the library of choice for image recognition. While it is battle tested and has bindings in many major languages, the two available Haskell bindings (Haskell is my language of choice) are under-resourced and incomplete. By selecting Haskell I knowingly set myself up to do more basic library work and potentially make less progress on the task at hand. Ultimately, I selected the CV library, grabbed a few papers, and got to work.

License Plate Recognition

My pipeline is informed by the papers I perused. Plate Localization uses an otsu threshold, filter blob with high areas, white hat, filter blobs of area outside of a range, dilation, and shape filtering (keep rectangular blobs). Potential plates are then extracted and cleaned by filtering based on the area, width/height relative to near by objects, and number of blobs. Finally, I segment all the blobs (sorted left to right) sending each one individually to GNU optical character recognizer.

Results

An example of a successful application starts with a typical image of a car in traffic:

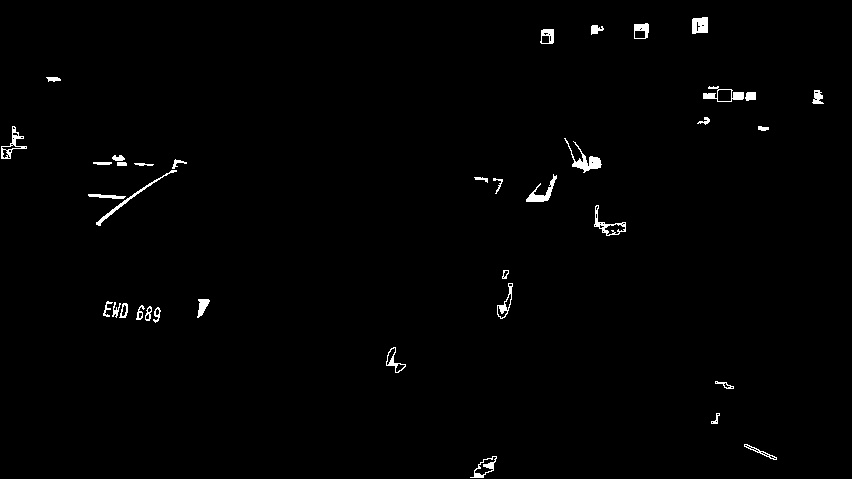

We then see how thresholding helps (while assuming the plate is dark numbers on a light background):

The white top-hat reduces many of the objects to skeletons, breaking some apart so we can consider them as separate blobs. This is important for some images that, when thresholded, connect a letter or two from the plate to the body of the car.

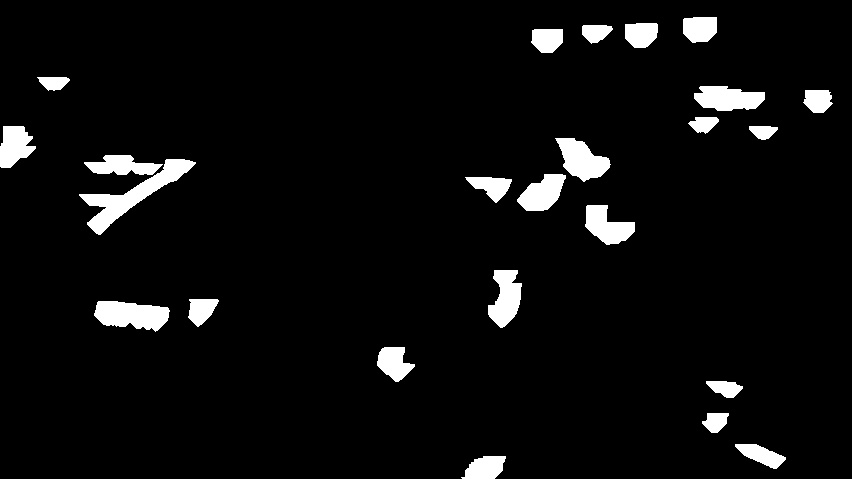

The size-filter gives us:

Now dilation allows us to connect the individual letters into a single blob. The areas that show up as white in the dilated image are checked to see if they contain between 3 and 30 separate blobs (in the thresholded image), if so then I consider this portion of the image as a potential plate.

With just a little more processing, such as comparing the sizes of the blobs to make sure they are approximately the same height, we end up with two blobs. After cleaning, here they are:

This license plate is properly segmented and GOCR tells me the plate is “F669’”, or “fY_ 68_ J” if given the letters all at once.

Issues

-

Of the portion of the week I spent on LPR, the time was divided between reading, learning and testing primitives, and modifying the CV library.

-

Unsurprisingly, the exact values I use for filtering are highly tuned to the images I was testing with at the time and the distances I assumed from the target. Using my high-resolution (non-phone) camera, the current software extracts the smaller texts such as the tag year and car model while tossing the plate number entirely. Some basic resizing would fix this issue.

-

While it out performs the other OCR systems I found, GOCR doesn’t perform as well as I would like for this task. I noticed some papers perform OpenCV template matching in place of OCR, which I intend to try in the future.